Osteoarthritis (OA) is a highly prevalent, disabling disease which places a tremendous burden on affected individuals as well as private and public health budgets.

Osteoarthritis (OA) is a highly prevalent, disabling disease which places a tremendous burden on affected individuals as well as private and public health budgets.

Osteoarthritis is a chronic condition of the synovial joint – most common type of movable joint in the body. The disease develops over time and most commonly affects the knees, hips and hands, and less commonly the shoulder, spine, ankles and feet.

For individuals, the physical and emotional impact of osteoarthritis can have a major impact on their life. Common physical symptoms include pain, stiffness and loss of function in the affected joint. For many this can make everyday activities difficult; such as going up and down stairs, getting in and out of a car or putting on socks / stockings.

The emotional impact of osteoarthritis can also be profound. Living with chronic pain and reduced mobility often restricts a person’s ability to participate in hobbies and social events which can have negative consequences for quality of life and mood.

In Australia osteoarthritis is the underlying diagnosis of 97% of all total knee replacement procedures and 89% of all total hip replacement procedures.

From a health budget perspective most of the direct costs are usually attributed to hospital stays and specifically elective orthopaedic surgery, with smaller proportions accounted for by medications, physicians visits and diagnostic procedures.

Osteoarthritis onset and progression

There are a number of modifiable and non-modifiable factors that influence the onset and progression of osteoarthritis.

General Osteoarthritis Treatment

Osteoarthritis, like many chronic diseases, has no single treatment or cure.

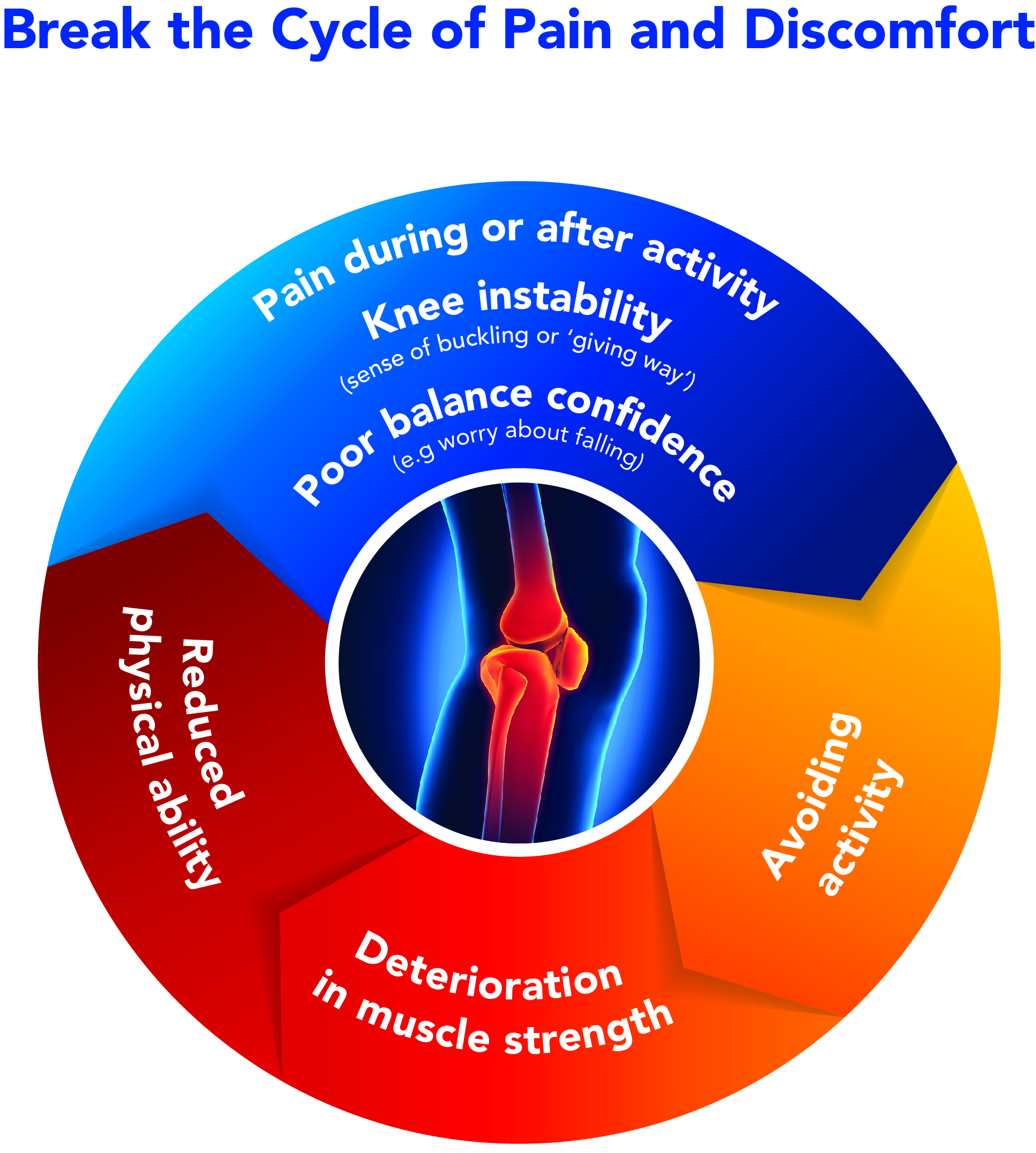

Best practice treatment of hip and/or knee osteoarthritis typically integrates a combination of interventions to break the cycle of pain and discomfort, with the aim of symptom relief, improving joint mobility and function, and optimising quality of life.

Clinicians recognise that to maximise the effectiveness of individual treatments it is best to use them as part of a package which incorporates many of the strategies together.

Australian and international treatment guidelines for people with Knee osteoarthritis include the following core treatments:

- Weight management

- Strength training

- Physical activity

- Self-management and education

Weight management

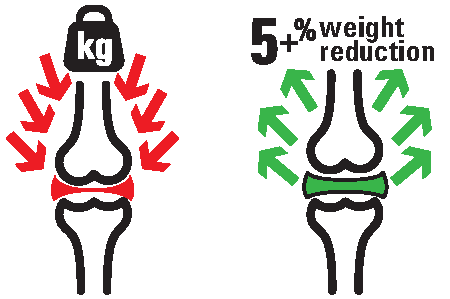

Recommend individuals who are overweight to achieve at least weight loss of 5% within a 20 week period for the treatment to be effective.

Secondly, research has found that a 10% or greater reduction in body weight over an 18 month period results in greater improvement in function and reductions in pain compared to those who lost 5% to 9.9% or less than 5% of their baseline weight.

Best practice osteoarthritis management typically combines multiple treatments and interventions (non-pharmacological and some pharmacological) that target the different symptoms and risk factors that contribute to the disease progression.

Strength training

Both weight-bearing and non-weight bearing resistance-based lower limb and quadriceps strengthening exercises are recommended. Group or individual programs have been found to provide similarly significant improvements.

Physical activity

Land-based exercise can provide clinically relevant short-term benefits for pain and physical function in knee osteoarthritis. Recent analyses included a range of different strength training, active range of motion exercises and aerobic activity with generally positive results which did not significantly favour any specific exercise regimens. For example tái chi has been found to give strong favourable benefits for pain and function in individuals with knee osteoarthritis.

Water based exercise can have small to moderate short-term benefits for function and quality of life, but only minor benefits for pain.

Self-management and education

Self-management education programs (SMEPs) aim to equip individuals with knowledge of their disease, as well as motivation and practical skills to relieve pain and reduce the impact of the disease on their life. These programs combine education with behavioural modification and empowerment techniques, and aim to increase adherence to treatment, promote decision making related to chronic disease management, and manage psychosocial impacts of disease such as anxiety, low self-image and/or confidence, depression and helplessness.

Complete Australian Government approved guidelines

Australian Government approved Guidelines for the Non-surgical Management of Hip and Knee Osteoarthritis July 2018.

Quick references:

- Hip / knee osteoarthritis management flow chart - page 15

- Weight reduction: - page 23 (significant benefit was noted with more than 5% weight reduction)

- Exercise- page 23 - 26

References

Hunter, D.J., et al., The individual and socioeconomic impact of osteoarthritis. Nature Reviews Rheumatology, 2014. 10(7): pp 437-41

Murphy, L., et al., Anxiety and Depression Among US Adults with arthritis: Prevalence and correlates. Arthritis Care and Research, 2012. 64(7): pp 968-976

Australian Orthopaedic Association, National Joint Replacement Registry, Annual Report 2013

Pisters, M.F., et al., Avoidance of activity and limitations in activities in patients with osteoarthritis of the hip or knee: a 5 year follow-up study on the mediating role of reduced muscle strength. Osteoarthritis and Cartilage, 2014. 22(2): PP 171-177

Nguyen, U.-S.D.T., et al., The impact of knee instability with and without buckling on balance confidence, fear of falling and physical function: the Multicentre Osteoarthritis Study. Osteoarthritis and Cartilage, 2014. 22(4): PP 527-534

Hunter, D.J., et al., The individual and socioeconomic impact of osteoarthritis. Nature Reviews Rheumatology, 2014. 10(7): pp 437-41

Messier, S., et al., Weight loss reduces knee-joint loads in overweight and obese adults with knee osteoarthritis. Arthritis and Rheumatism, 2005. 52(7): pp 2026-2032

Pottie, P., et al., Obesity and osteoarthritis: more complex than predicted! Ann Rheum Dis, 2006. 65(11): p. 1403-5

Distel, E., et al., The infrapatellar fat pad in knee osteoarthritis: an important source of interleukin-6 and its soluble receptor. Arthritis Rheum, 2009. 60(11): p. 3374-7.

Guideline for the Non-surgical Management of Hip and Knee Osteoarthritis (2009). Approved by NHMRC 23 February 2009. Published by The Royal Australian College of General Practitioners

McAlindon, T.E., et al., OARSI guidelines for the non-surgical management of knee osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis and Cartilage, 2014. 22; pp 363 – 388

Messier, S.P., et al., Effects of intensive diet and exercise on knee joint loads, inflammation, and clinical outcomes among overweight and obese adults with knee osteoarthritis: the IDEA randomized clinical trial. JAMA, 2013. 310(12): p. 1263-73.

While not everyone who has osteoarthritis is overweight, being overweight is considered a great risk factor for the development and progression of osteoarthritis.

While not everyone who has osteoarthritis is overweight, being overweight is considered a great risk factor for the development and progression of osteoarthritis. Individuals who experience knee buckling (‘giving way’) or sensations of knee instability generally experience greater fear of falling, poor balance confidence and activity limitations. All of which can contribute to the individual avoiding being physically active.

Individuals who experience knee buckling (‘giving way’) or sensations of knee instability generally experience greater fear of falling, poor balance confidence and activity limitations. All of which can contribute to the individual avoiding being physically active.